BEHAVIOUR

Adaptation to the Environment

It is not the most intellectual of species that survives; it is not the strongest that survives. it is the one that is able best to adapt to the changing environment.

(Leon Meggison)

Survival strategies

The Darwinian principle of survival of the fittest is based on adaptation to the environment. The more varied and changing the environment, the greater the need to adapt, both physically and mentally, the tools and skills necessary to survive and flourish. Different species adapt to their different needs by developing skills that are needed and neglecting others. All animal species, including humans, can be expert at the things that matter, useless at others. The albatross can return to its nest having roamed for months over the featureless southern ocean yet will fail to recognise its own chick if it has fallen out. A human dropped in the southern ocean without chart and compass (or GPS) would be completely lost.

All sentient animals are born with an inherited operation manual and toolkit of instinctive physical and mental resources designed to promote survival and wellbeing. Animals with sentient minds build on this birthright to develop knowledge and understanding of their physical and social environment and hone their special skills. This enhances their ability to cope but can increase their potential to suffer if they fail. This may arise because the environmental challenges are too severe, complex or prolonged, or if they are constrained in an environment that restricts their ability to exhibit coping behaviour.

For a species to prosper in the wild, it must behave in such a way as to sustain a balance between production and losses from predation, disease or exhaustion of resources. Here are some examples to consider.

Herbivores: Wildebeeest

Nutrition: navigation skills and memory enabling wide ranging foraging and access to water. Migration en masse through high-risk sites (rivers)

Reproduction: synchronised calving

Security: fitness of the herd ensured by synchronising high risk events, to outnumber the chances of predation.

Carnivores: Peregrine falcon

Nutrition: hunting skills essential, require education

Reproduction: egg numbers constrained by access to food resource

Security: chicks need secure nests until old and skilled enough to hunt.

Omnivores: Badgers

Nutrition: omnivorous, year-round

Access to food.

Security: few predators (cars). Risk of over-population

Management: population control?

Omnivores: Humans

Nutrition: omnivorous

Reproduction: controllable

Resources: intermittently and locally insufficient and globally unsustainable at current rates of consumption

Social Strategies

Animals that share the same habitat may compete, collaborate or simply coexist. Hunters, e.g. the large carnivores regard all animals outside their immediate family either as meat or as competitors. Species that live in social groups, usually for reasons of security, achieve, at least, a system of reasonably peaceful coexistence, typically a hierarchy. Many social species display more complex behaviour such as communication, cooperation and social learning. We can ponder as to how these reflect deeper expressions of the sentient mind; friendship, empathy, compassion, love, but we can be sure that, through education, they promote the mental development, and through companionship, the emotional wellbeing of the group.

Social hierarchies: the pecking order

The social order within a community is most stable when all individuals are (reasonably) satisfied with their place (a depressing conclusion for a libertarian) Establishment of the social order may be instinctive, commanded, or acquired. Members of a wolf pack are instinctively subordinate to the alpha breeding pair. Human members of the armed forces are programmed to obey orders. Chickens acquire their place in a stable pecking order through interactions that may, at first involve active aggression but are subsequently resolved through ritualised gestures. In pigs, the hierarchy is unstable so the risk of conflict is greater.

Communication

Communication describes the transmission and reception of emotion and information through all the special senses: sight, sound, smell and touch. Species differ in how they rely on these media in ways that reflect their value within their natural environment. They are proficient at the skills that matter most, poor at those that matter least. Humans rely on sight and sound to communicate information using words, but, by dog standards, we have a dismal ability to identify and discriminate information through scent. Birds and flying insects use sight to communicate sexual signals and flight controls. Many species communicate sexual signals through smell (pheromones). Visual signs, facial expression, body language, communicate emotions: aggression, fear. Touch can signal companionship and compassion. Some examples are illustrated here. Think up others to add to the list.

SIght

information: education

navigation: pigeons ‘map reading’

flight commands (starling murmuration)

education

Emotion

sexual signalling: bird displays

aggression: fear/submission

Sound

Information

echolocation: bats

communication: whales

Emotion

Fear, pain

Smell

Information

Sniffer dogs

Navigation: e.g. salmon

Emotion

Fear

Sexual attraction, pheromones

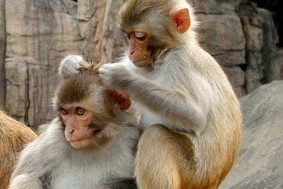

Touch

Information

important when vision is limited

Emotion

Companionship, empathy?

Cooperation and empathy

If social animals are to thrive, they must cooperate. At the simplest level, cooperation among ants relies on a set of instinctive reactions to simple signals. Flexible cooperation requires the power of mental formulation: not only to interpret the actions of others but also their expressions and behaviour as indices of their intention and emotional state. This degree of sentience would appear to require empathy, based on a recognition of self and non-self: Theory of Mind in animals. This makes it possible for an animal to recognise that you too are a sentient being who make not think and feel as I do. At the deepest degrees of sentience this can be expressed in forms of affiliative behaviour, concern for others. However, it can only be described as altruistic if it is directed to others outside the family group

.

Social learning, education and culture.

Social learning is a major contributor to the development of sentient minds, especially in vulnerable species for whom the trial-and-error approach to self-education carries a high degree of danger. Naïve animals in social species acquire most survival skills from observation and mimicry. The behaviour of individuals within species with the capacity for mental formulation can be influenced as much by the acquired culture of the local population as by the genetically blueprint for the species. This is beautifully expressed in the music of songbirds (Brainar & Doupe 2002). Moreover, there is good evidence that parent birds teach their offspring survival skills acquired within their lifetime (e.g. to avoid poisonous foods Nicol and Pope 1996,

Territorial Behaviour and Tribalism

For most species whose survival, security and wellbeing in their natural environment depend on group living, the group is likely to equate to the extended family, protecting the fitness of their genetic inheritance against competition from other societies within their shared habitat. Chimpanzees are fiercely aggressive to competing tribes. Curiously, bonobos, in similar habitats, maintain the stability and well-being of their population by making love not war. Large grazing animals on open range compete less because there is less need for competition. Problems of conspecific aggression in farm animals, pigs and chickens, may (not always) be attributed to management systems that make it impossible for the animals to establish stable social groups.

Behaviour Science

We can never really know how other species feel and think. However, we can observe how they behave in their natural environment, and we can set them questions designed to help us understand why they do what they do. This is motivation analysis

Observation of natural behaviour

Question: identify needs for resources (diet, physical and social environment) and actions performed to achieve physical and mental wellbeing

Outcome: better understanding of how to permit animals to address their needs wherever we disrupt their natural environment to suit our own needs for food, companionship, sport, safety or science.

Motivation analysis

Controlled experiments designed to establish animal attraction for, aversion from or indifference to specific resources

Preference testing:

The animal is given a choice between two (or more) resources, e.g. food, comfort, social environment and invited to express a preference. Examples:

Attractive v. Aversive: enriched v. barren cages for hens, rats in labs.

Unknown: choice of flavours in cat foods

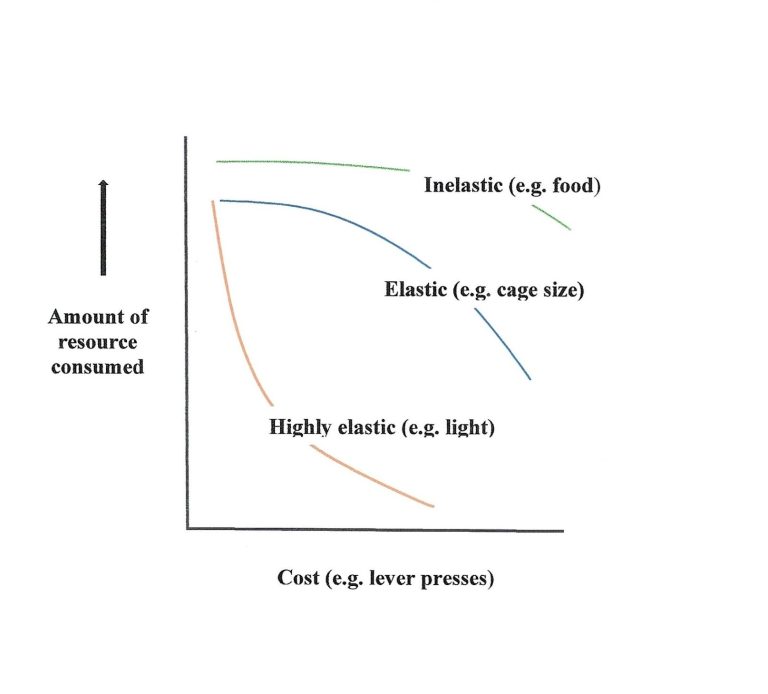

Consumer Demand theory

Simple preference testing cannot distinguish between choices that are of importance to welfare and those that are trivial. We can measure the importance of a resource by asking the animal how much an animal is prepared to pay (e.g. number of bar presses) to obtain that resource. Specific resources can be identified as more or less price elastic. The diagram illustrates examples of the price that caged hens may be prepared to pay for resources of food, space and light. The demand for food is inelastic and will only begin to fall when the price becomes very high. Demand for light is extremely elastic. The former is a necessity, the latter a relative luxury. (Dawkins 1993, Mason et al 1998)

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details and accept the service to view the translations.