Animal Sentience and Welfare: A Self-help Guide John Webster

WELCOME

For more than 50 years my thoughts and deeds have focused on animal sentience and animal welfare, viewed, so far as possible through their eyes, not ours. I offer this site as an introduction to these things, as I understand them, for all who care, whatever their age and experience. My approach is based on the principle of Reverence for Life. My rules of engagement are constrained by the principles of sound science. Together, these drive me to the conclusion that all life is worthy of respect and no species is better or more worthy of our respect than any other. My aim throughout this brief introduction to the philosophy, science and practice of animal welfare is not to suggest what you should think but to present structures upon which you can develop your own thoughts and interpret your experience. There are links for those who want to dig deeper. I have put these ideas on a website because those with whom I most want to share my ideas are those who cannot afford my books.

CONTENTS

HOME About me Ethics Planet Husbandry Contact me

SENTIENT MINDS The five Skandhas of sentience Sensation and emotion BEHAVIOUR Social and survival strategies Behaviour science WELFARE Welfare science Welfare in Practice Farm Animals Animals in Sport and in the home Laboratory animals Solutions

FURTHER READING

ABOUT ME

At the age of about ten, having read the Dr Doolittle books, I decided

that I wanted to be a vet and spent most of my school holidays with

a vet very much in the James Herriot mode, out on farm visits and

almost never in the surgery. When I began my studies at St John’s

College, Cambridge, the limit of my ambition was to spend my life

looking after cows. At university however, I was bitten by the science

bug and inspired in particular by Sir John Hammond who revealed

how much science could contribute to the production, health and

wellbeing of farm animals on an international scale. This struck a chord.

I was advised that if I wanted to make any impact, I would need a PhD

first so, after a short time in practice, I applied to the Hannah Dairy

Research Institute in Ayr to join a study of climatic stress in cattle. My aim was to study heat stress and do much of my work in Africa. I was, however, allocated to cold stress, so (to cut things short) found myself, after three years at the University of Alberta in Canada, teaching cowboys and studying stresses on cattle exposed to the most severe cold, (which, having adapted, they tolerated surprisingly well). Later I was invited to join the Rowett Institute in Aberdeen as Head of the Energy Metabolism department, to study animal production in the context of energy flow through the whole spectrum from plants to animals to food for human consumption. This provided an excellent foundation for my lasting interest in nutrition and Planet Husbandry.

I was appointed Professor of Animal Husbandry at the University of Bristol in 1977. My arrival at the Bristol Vet School coincided with a tidal surge of concern as to the welfare of farm animals, especially those reared in highly intensive conditions: hens confined in battery, pregnant sows in crates and veal calves in wooden boxes. This had been stimulated in large part by the publication of Ruth Harrison’s seminal book ‘Animal Machines’. This led to the establishment of the Brambell Commission of enquiry, whose main recommendation was that every animal should ‘without difficulty, be able to stand up, lie down, turn round, groom itself and stretch its limbs’. These recommendation as to minimally acceptable standards for physical comfort and natural behaviour became known as the ‘Five Freedoms’. I had experience of intensive systems for the production of white veal by calves reared on all-liquid diets and had been arguing with some force that restricting behaviour was just one element of the welfare problem. White veal production was appalling by every measure, improper nutrition, chronic discomfort, an unacceptable prevalence of disease, extreme behavioural restriction and chronic anxiety attributable to a total absence of conditioning by experience so that the slightest sudden sound could cause mass panic. This led me to propose a more comprehensive set of Five Freedoms: four freedoms from, namely hunger and thirst, physical and thermal discomfort, pain, injury and disease, fear and stress, and one freedom to, then described as freedom to perform natural behaviour, but, on reflection, better described as freedom of choice. I was invited to become a founder member of the UK Farm Animal Welfare Council, who adopted these five freedoms that have now become an international standard.

One of my first projects on arrival at Bristol was to establish a unit for the scientific study of farm animal welfare, at that time a rather mushy enterprise. I had the good fortune to appoint Christine Nicol, then newly emerged from a DPhil in behavioural science at Oxford. Christine’s skills were immediately apparent and complementary to mine. At the time of our departure from Bristol, we had established one of the major world centres for the study of animal welfare and behaviour.

The themes outlined on this site are developed in three books published under the auspices of the Universities Federation for Animals Welfare UFAW: Animal Welfare, A Cool Eye towards Eden, Limping towards Eden and Understanding Sentient Minds and why it matters

________________________________________________________

ETHICS

‘The great fault of all ethics hitherto has been that they believed themselves to have to deal only with the relations of man to man. In reality, the question is’ what is his attitude to the world and all that comes within his reach?’’

‘Ethics is nothing other than Reverence for Life. Albert Schweizer

MY RULES OF ENGAGEMENT

The needs of a sentient animal are defined entirely by its own physical and emotional phenotype, its environment and its education, and these are independent of our own definition of the animal as:

Wild: subsets, game, (e.g. fox) vermin (rat), protected (badger)

Domestic: subsets, pet (dog), farm (pig), sport (horse)

Animals may be domesticated but there is no such thing as a domestic animal.

Bioethical principles

Two moral principles that have stood the test of time.

The Categorical Imperative: Each individual should act according to the maxim ‘whereby you can, will that your actions should become a universal law’ (Immanuel Kant)

This describes Beneficence (do good and do no harm) and justifies utilitarianism, promotion of wellbeing, or ‘the greatest happiness of the greatest number’ (Jeremy Bentham). Bentham extended this principle to non-human animals. ‘the question is not can they think …. but can they suffer?

The Golden Rule. Deontology, the science of duty. ‘Do as you would be done by’.

This respects the principle of Autonomy, which gives equal rights to others. Both principles apply to our actions in regard to all sentient species. The aim should be to promote, so far as possible, Justice, the wellbeing of the population and the autonomy of each individual.

NATURE'S SOCIAL UNION

The pursuit of justice for humankind ('Equal Rights') requires us to to adapt Hobbes' principle of the Social Contract whereby, in order to acquire the right to avoid lives that are nasty, brutish and short, each party has a responsibility to contribute to the general welfare and accept some restrictions on personal behaviour. However, Animal Rights cannot be discussed in the same way as Human Rights, not least because the animals cannot contribute to the argument. It is helpful to regard sentient animals and, indeed, the whole living environment, in the same way that we regard newborn babies, as Moral Patients. We are the Moral Agents. We have a responsibility to them but they have no responsibility to us.

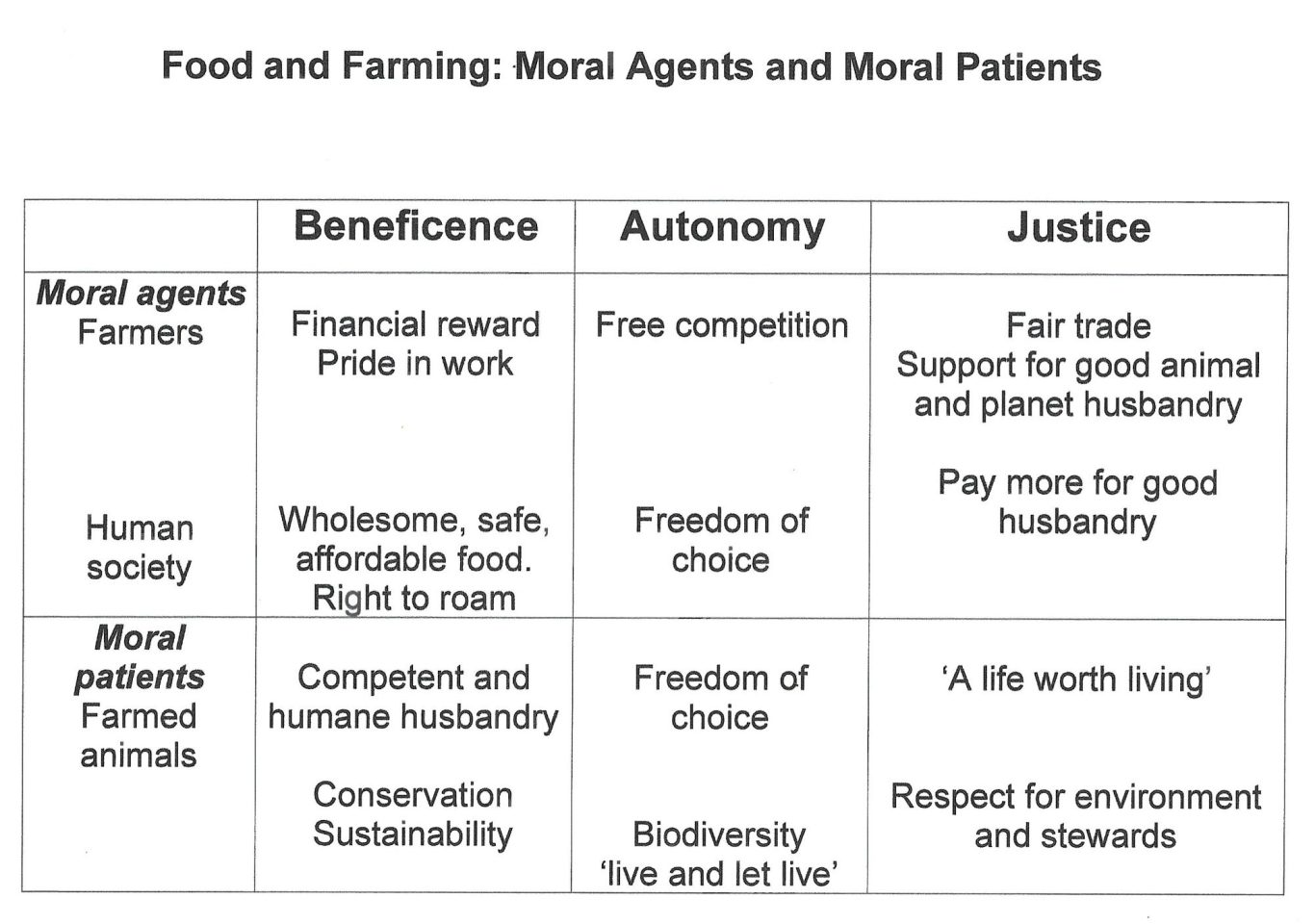

The aim is justice for all: moral agents and moral patients. This involves compromise. If human society are to expect access both to a free choice of wholesome, safe, affordable food and the right to roam, they must expect to pay a fair price for all commodities and prepared to pay more for food produced to quality assured high standards of animal husbandry and welfare. The farm animals need more than just competent and humane husbandry (utilitarianism) they have a right to expect a sufficiently enriched, interesting environment to permit them freedom of choice (Five Freedoms). If we are to preserve the quality of the environment we must give respect to the stewards of the environment. I discuss this below under the title Planet Husbandry.

THE ETHICAL MATRIX

Farm Animals and Food Production

If we are to apply the pure and fundamental principles of beneficence and autonomy to the real-life problems of animal welfare we need a pragmatic, bottom-up approach that identifies a specific practical issue then constructs an analysis of relevant moral issues by a process of induction.It can take the form of an Ethical Matrix that identifies Beneficence and Autonomy as moral inputs and Justice as the moral outcome. A structure for the ethical analysis of food and farming is shown below. For a more complete description of the application of the matrix to ethical issues relating to our rearing of sentient animals on farms for food, and in laboratories for scientific procedures see Webster 2022.

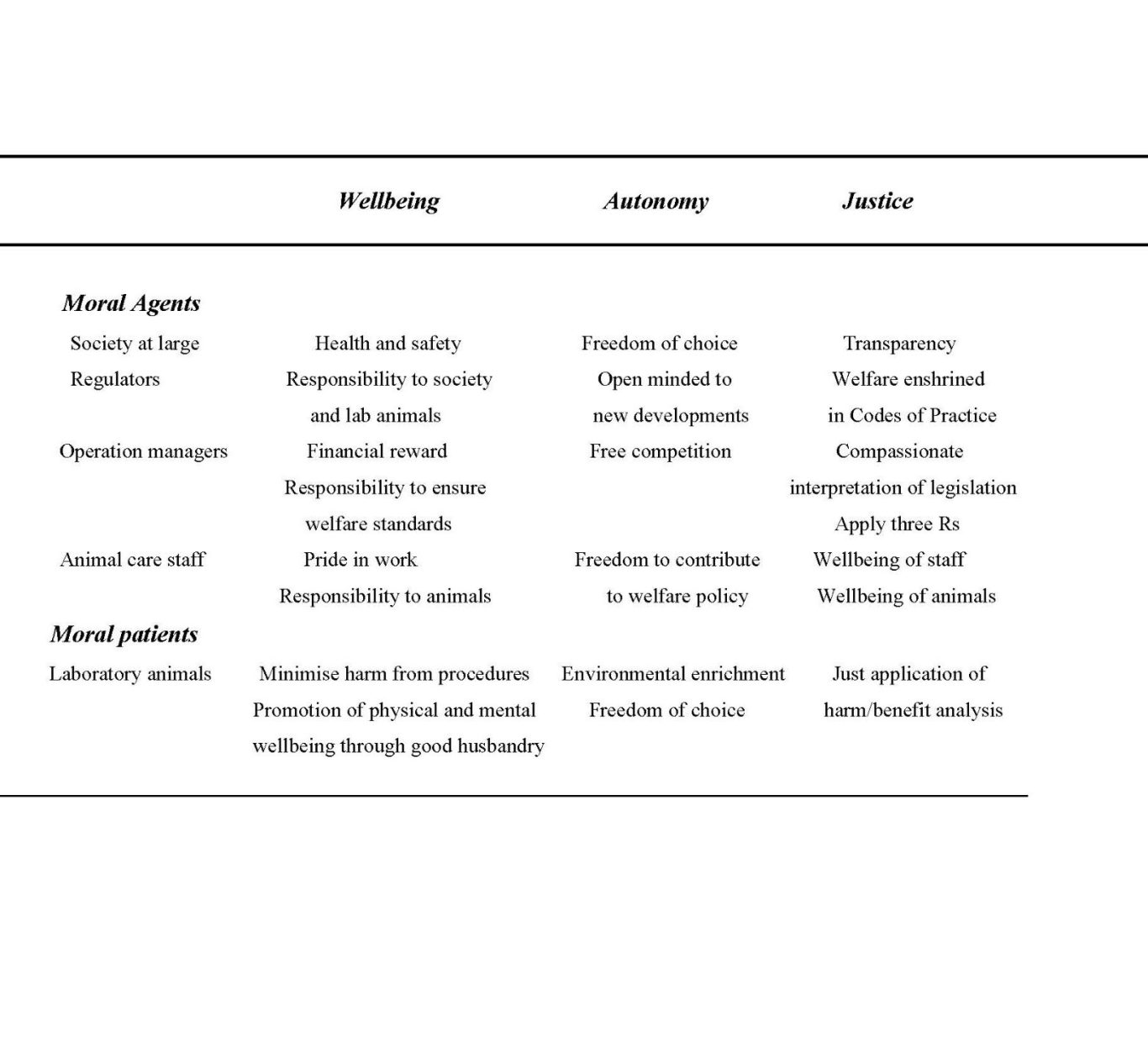

Ethical Matrix: Laboratory Animals

Humans carry out experiments on animals to advance science but most are used for reasons of health and safety, testing medicines, household products, garden sprays (etc) for evidence of toxicity. The Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 states that 'procedures using laboratory animals should only be allowed subject to a harm/benefit analysis where the cost to the animal is terms of 'pain, suffering, distress or lasting harm' can be justified in terms of the potential benefits to humans or other animals. The ethics of this Act are, of course, confounded by the fact that the benefits accrue to us and the harms to them, the moral patients. The principle that underpins the conduct of these scientific procedures is that of the 'Three Rs' : Refinement, Reduction and Replacement (Russel and BIrch 1959),

Replacement: Is it possible to achieve the scientific objective without use of live animals?

Reduction: what is the least number of animals needed to achieve the scientific objectives?

Refinement: (when the other options are not open) choice of procedures likely to minimise harm, or (possibly) choice of less sentient species. As we shall see, this latter proposal is difficult to guarantee.

The more recent EU Directive (2010/63/EU) .carries a similar message. These directives have greatly improved the welfare of laboratory animals, not least because they compel those working with animals both directly and at a distance to give more thought to how they feel. The following table applies the Ethical Matrix to the consider the needs of the moral patients and the needs and responsibilities of the moral agents: those directly involved in the trials, the legislators who set the rules and those who derive the benefits in terms of health and safety; i.e. all of us.

I could expand on the outlines of this Table but suggest you may gain more from thinking about it yourselves

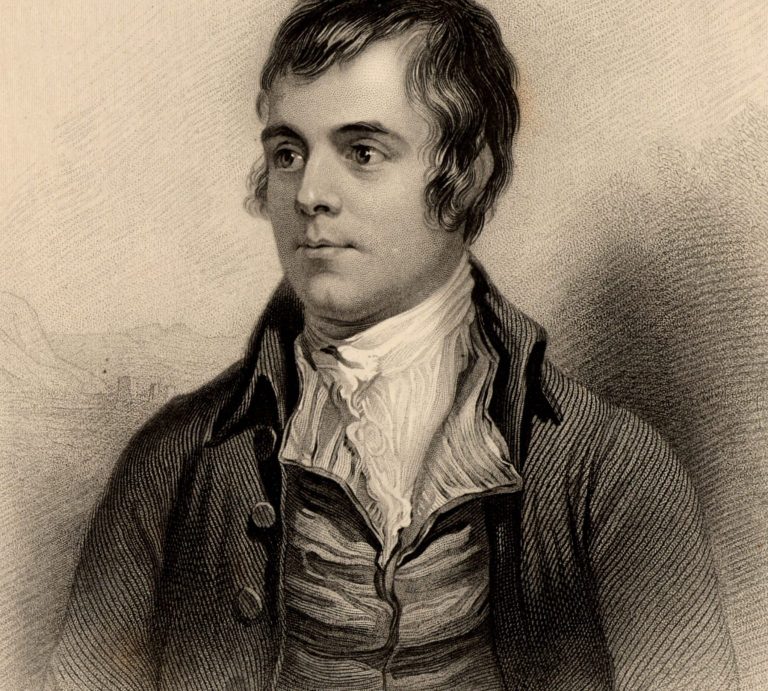

‘I’m truly sorry Man’s dominion

has broken nature’s social union

And justifies that ill opinion, that makes thee startle

at me thy poor earthbound an’ fellow mortal’

Robert Burns

Planet Husbandry: Sentient Animals in the living environment.

My approach to this examination of our relations with the sentient animals seeks to be loving without being sentimental, scientific without being arcane. It is based on two central pillars of good sense. The moral case lies with Albert Schweitzer: ‘the great fault of all ethics hitherto has been that they believed themselves to have to deal only with the relations of man to man. In reality, the question is’ what is his attitude to the world and all that comes within his reach?’ The scientific case rests on the irrefutable Darwinian principle that'it is not the most intellectual of species that survives; it is not the strongest that survives; it is the one that is able best to adapt to the changing environment'. Successful adaptation of any species to the environment is achieved by maintaining its genetic inheritance as a stable contributor to a sustainable ecosystem. According to this strict Darwinian classification, the human species has, until recently, managed reasonably well but over the last 100 years, thanks, to a large extent, to our exploitation of fossil fuels, we have broken free from the rules and constraints of ecology. Now we are all experiencing the consequences of our failure to be a stable contributor to a sustainable ecosystem, in the form of climate change, deterioration of soils and extinction of animal species through loss of habitat. Our insatiable appetite for food of animal origin and its consequences for livestock farming must carry much of the blame. This is too big a subject to present in detail here: I deal with it elsewhere in ‘Animal Husbandry Regained: the place of farm animals in sustainable agriculture’ (Webster 2013). A core message from this complex story is that farmed animals were stable contributors to a sustainable system when their needs for food and sustenance were largely complementary to, rather than in competition with ours. Ruminants grazed food we could not digest, mostly on land we did not own; pigs lived on food we discarded, poultry contributed to our nutrition, health and hygiene by scavenging for scraps and insects. I am not simply making an emotional appeal to go back to ‘the good old days’. I have shown, for example, that the modern dairy cow (by virtue of much hard work) can produce more food energy and protein for human consumption than she eats in the form of food suitable for human diets (Feed conversions). We could support a substantial pig industry on the discard of food from our supermarkets.

We cannot go on as we are. If we do, the most disastrous consequences in the short term will be to other life forms, as we progressively destroy them to promote our own interests. However, in the longer term, it is we who will be destroyed by the inescapable rules of Darwinian logic. This states that while it is in the primitive interests of all species to convert all matter into themselves, those that survive, consciously or otherwise, are those that achieve a stable position within the ecosystem. If we humans can achieve this, we too shall survive. If we fail, the planet will manage without us.

The principle of Reverence for Life commands us to avoid destruction of habitat and extinction of species and, at the same time, offer 'a life worth living' to the animals (the moral patients) with whom we share the planet. This assumes greatest importance in the case of the food animals. To satisfy our own tastes we rear approximately 500 million broiler chickens per year, fed almost entirely on food that could support ourselves. Today supermarket frozen chicken can be cheaper than dog food. In the interests of our health, their welfare and that of the planet we need to add value to the food from farmed animals. The adage ‘Eat food, not too much, mostly plants’ is incontestable. However, ‘only plants’ is an ecological no-no. We need to acknowledge that, in a sustainable system, plants (and the soil) need animals just as much as animals need plants. The destruction of arable land 'supported' by constant application of inorganic fertilisers is becoming critical. Extensive systems based on grass-fed ruminants cannot compete with factory farming when measured by short term indices of productivity and they certainly cannot meat our present demands for meat and dairy products but they can be sustainable (emergy analysis) Moreover, to my eyes, they are usually associated with good welfare. When I travel through classic beef cow country in the west of England and observe Ruby Red cows relaxing with their calves in 12-month green pastures, this seems to me to about as idyllic a life as any domesticated animal could ever wish for.

Complementarity: Sharing our Resources

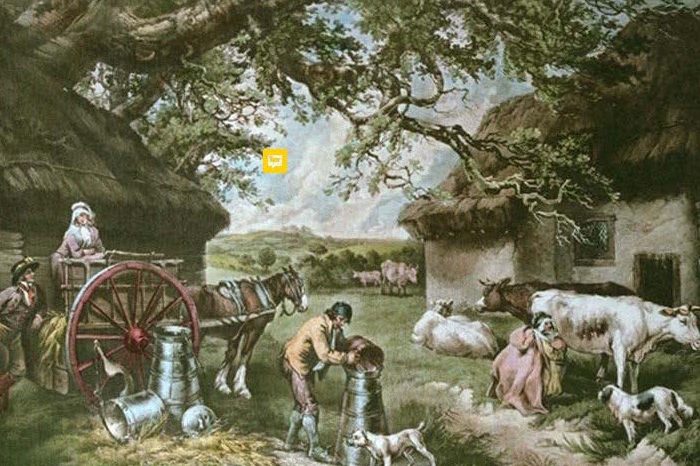

Traditional

All parties contribute

Not a scrap wasted

Modern

Agroforestry in Brazil.

Grass between trees is grazed or cut for cattle feed

Eccentric

Contact me

ajohnfwebster@gmail.com

This is a living document. I welcome comments and suggestions. Whether or not they find their way in here, I shall do my best to respond personally

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details and accept the service to view the translations.